Big Tech’s $364B Hypothesis Meets the $650B Reality

Six months ago, I wrote that Big Tech’s AI infrastructure spree was less a strategy and more a very expensive act of faith. The thesis was simple: $364 billion in annual CapEx with no clear path to ROI isn’t engineering. It’s hope with a procurement budget.

I expected pushback. I expected the numbers to be revised. I did not expect them to nearly double.

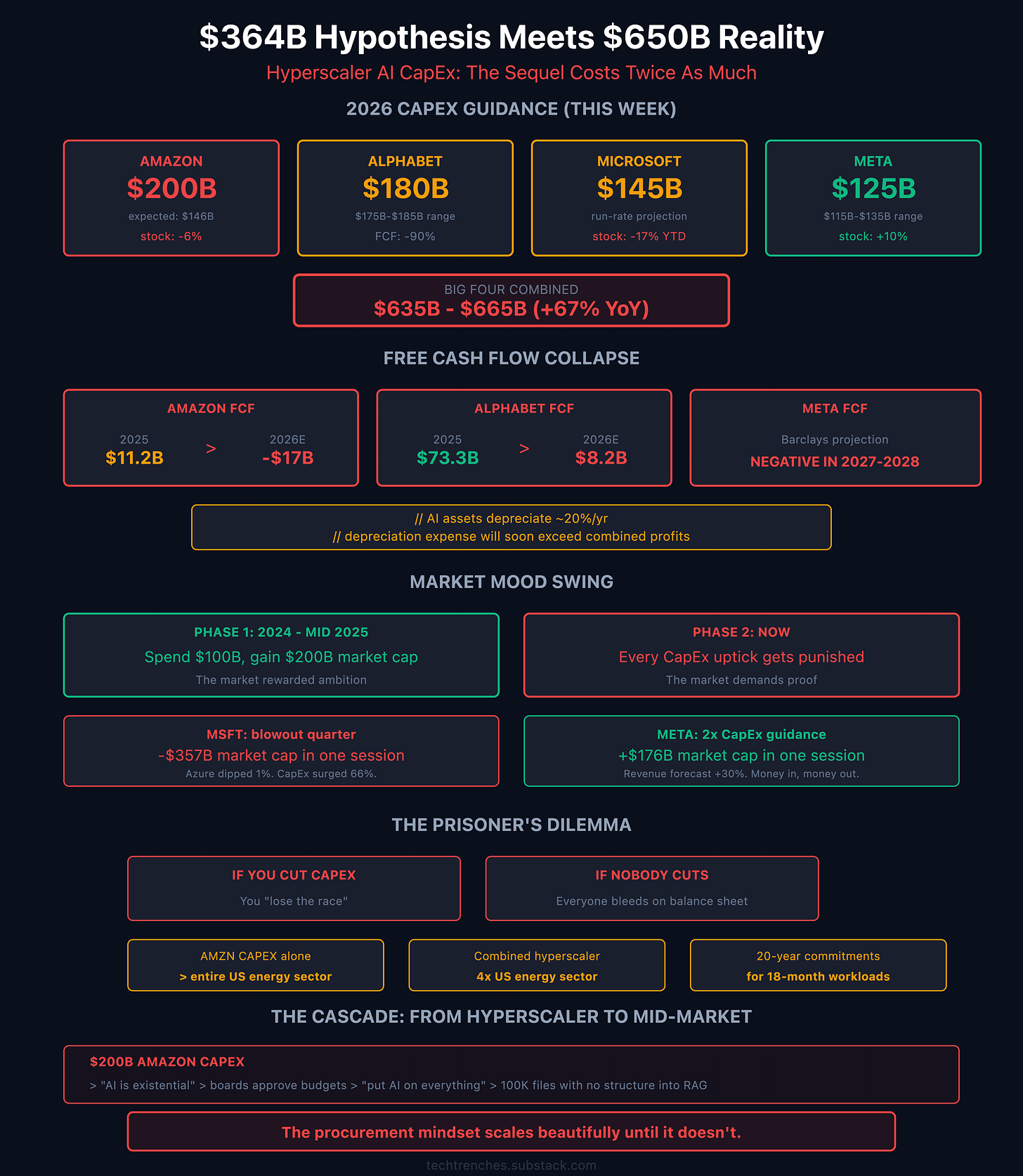

Last week, Amazon dropped the number that completed the picture: $200 billion in capital expenditures for 2026. That’s $44 billion above what Wall Street expected. The stock fell 6% in a single session on trading volume 306% above its three-month average. Amazon filed with the SEC the next day, warning it may need to raise equity and debt to fund the build-out.

Amazon wasn’t alone. Alphabet guided $175 to $185 billion. Meta said $115 to $135 billion. Microsoft’s run rate puts it on pace for $145 billion. The Big Four alone: $635 to $665 billion. A 67% to 74% spike from $381 billion in 2025.

Add Oracle, and the Big Five cross $700 billion.

The most expensive engineering experiment in history just got a sequel. And the sequel costs twice as much.

The Curve That “Couldn’t Happen”

When I wrote the original piece in September 2025, critics said I was cherry-picking. Companies knew what they were doing. Demand was real. Scale would solve everything.

For two straight years, Wall Street’s CapEx estimates have come in low. At the start of both 2024 and 2025, consensus implied roughly 20% annual growth. Actual spending exceeded 50% both years. Goldman Sachs projected $500 billion-plus for 2026. They were too conservative.

The industry quietly moved from “we’re investing for growth” to something much larger: restructuring the physical substrate of the internet around a single class of workload. Capital intensity has surged to historically unthinkable levels: Oracle’s most recent quarter hit 57% of revenue, Microsoft reached 45%. These aren’t growth investments. They’re multi-year capital commitments with depreciation clocks already ticking.

The Free Cash Flow Collapse

Here’s where the math gets uncomfortable.

Amazon’s trailing-twelve-month free cash flow already cratered from $38.2 billion to $11.2 billion. With $200 billion in 2026 CapEx, Morgan Stanley projects it goes negative: minus $17 billion. Bank of America sees minus $28 billion.

Alphabet’s free cash flow is projected to plummet nearly 90%, from $73.3 billion to $8.2 billion. Barclays is now modeling negative free cash flow for Meta in 2027 and 2028: “somewhat shocking to us but likely what we eventually see for all companies in the AI infrastructure arms race.”

Microsoft is the only hyperscaler maintaining positive FCF trajectory, with a projected 22% margin. But Azure growth slowed from 40% to 39% while quarterly CapEx surged 66% to $37.5 billion. The stock is down 17% year-to-date, the worst performer in the group.

Combined cash reserves across the four leaders: over $420 billion. That sounds like a buffer until you realize that AI assets depreciate at roughly 20% per year. At current CapEx levels, annual depreciation expense will soon exceed combined profits.

These companies aren’t just spending more than they earn. They’re spending more than they can fund internally, and the debt markets are stepping in to bridge the gap.

The Market Mood Swing

Phase One (2024-mid 2025): any AI announcement earned more market cap than it consumed in CapEx. Spend $100 billion, gain $200 billion in valuation. The market rewarded ambition.

Phase Two (now): every CapEx uptick gets punished. Microsoft reported a blowout quarter, 17% revenue growth, $50 billion in quarterly cloud revenue for the first time ever, and lost $357 billion in market cap because Azure growth dipped one percentage point. Amazon beat on revenue and lost 6% because CapEx guidance was $44 billion above consensus.

The contrast with Meta is instructive. Meta guided $115 to $135 billion in CapEx, nearly double 2025. The stock surged 10%. The difference? Meta simultaneously lifted revenue growth forecast to 30%. It showed the money going in and the money coming out.

The core question from investors is now explicit: who exactly will pay back these hundreds of billions, and when?

The Strategic Trap

The hyperscalers have built themselves a prisoner’s dilemma at planetary scale.

If you’re the only one cutting CapEx, you “lose the race.” If nobody cuts, everyone bleeds on the balance sheet. The entire sector becomes dependent on a single assumption: that AI workloads will generate enough revenue to service infrastructure that’s already built and already depreciating.

The entry cost for “AI sovereignty” is now so high that only existing hyperscalers and sovereign states can play. Infrastructure is becoming an oligopoly for physical reasons: power grids, cooling water, land, and political access to build. Amazon’s CapEx alone exceeds what the entire publicly traded US energy sector spends to drill, extract, refine, and deliver. Combined hyperscaler 2026 CapEx is more than 4x the entire US energy sector. These are 20-year physical commitments being made to support workloads that change every 18 months. You can’t iterate on a data center the way you iterate on code. You can’t A/B test a power purchase agreement.

And the dependencies stack. Forty-five percent of Microsoft’s $625 billion in remaining performance obligations is tied to OpenAI. When your single largest customer is a company burning cash with no clear profitability timeline, your CapEx bet is stacked on someone else’s CapEx bet.

The Engineering Reality

I’ve been watching what this dynamic does inside actual engineering organizations. The pattern is consistent, and it cascades all the way down.

Inside Big Tech, pressure shifts from “build things users love” to “ship AI features that justify already-committed infrastructure.” We’re building a new kind of feature factory: a demo factory designed to rationalize sunk infrastructure costs to boards and investors.

But the spending frenzy doesn’t just distort Big Tech. It creates a gravity field that pulls every company into the same pattern. I see it in our consulting work every week.

One client came to us wanting to build a RAG system across their entire knowledge base. The scope: 100,025 files, 43,063 folders, 72.1 gigabytes. No consistent structure. No permission model. No taxonomy. Just “put AI on everything.” During the requirements validation session, we managed to convince them to start with a single department and a well-defined use case. But the instinct was clear: spend first, figure out the problem later.

Another client wanted “AI integration across all processes.” Every system connected. Every workflow touched. When we asked what specific outcome they were optimizing for, what metric would tell them it worked, they didn’t have an answer. They had budget approval, vendor excitement, and a board presentation that said “AI transformation.” What they didn’t have was a problem statement.

These aren’t stupid people. They’re smart operators caught in the same gravitational pull as the hyperscalers. The procurement mindset cascades from $200 billion Amazon announcements all the way down to a mid-market company trying to RAG-index 72 gigabytes of unstructured chaos.

The engineering loop got inverted at every level. The normal sequence is: identify the problem, then build infrastructure to solve it. What’s happening now is the opposite. We build first and search for use cases later. At hyperscaler scale, that means $650 billion in steel and GPUs. At company level, it means integrations, tokens, and vendor contracts thrown at a vague sense of urgency.

The Endgames

I see three possible outcomes, and they’re not mutually exclusive.

Soft landing. AI services find broad, profitable demand fast enough to service the CapEx and accumulated debt. This requires AI to generate trillions in new economic value, not billions. The timeline is aggressive.

Infrastructure hangover. Chronic overcapacity leads to write-downs, consolidation, and distressed sales of data center assets. This is the fiber-optic bubble parallel that nobody wants to discuss, even though the IEEE ComSoc blog is already drawing the comparison explicitly.

Political fork. Governments either prop this up through subsidies and public workloads, or constrain it through energy regulation, water restrictions, and local opposition. The EU is already moving on the regulatory side.

Why This Matters Now

With $650 billion on the table, markets punishing CapEx announcements, and free cash flow collapsing across the board, the original piece reads less like a hot take and more like a blueprint of the failure modes we’re now entering.

The uncomfortable truth hasn’t changed. It’s just gotten more expensive. When an entire industry simultaneously chooses to spend rather than optimize, it reveals something broken in how engineering problems get solved.

Every engineering leader I know is asking the same question: are we building infrastructure for real demand, or are we building monuments to institutional momentum?

The numbers will answer that question within the next 18 months. The rest of us need to be ready for either outcome.

Subscribe for weekly insights from the trenches of engineering leadership. Real problems, practical solutions, no corporate optimism.