The First Full-Scale Cyber War: 4 Years of Lessons

December 12, 2023. 7:00 AM Kyiv time. Kyivstar, Ukraine’s largest mobile operator with 24.3 million subscribers, goes silent. Mobile service, internet, air raid alert systems in Kyiv and Sumy regions. All offline.

Within hours, Sandworm hackers destroyed 10,000 computers, 4,000+ servers, all cloud storage, and backups. Illia Vitiuk, head of SBU’s cybersecurity department: “This is probably the first example of a destructive cyberattack that completely destroyed the core of a telecoms operator.”

The hackers had been inside since May 2023. Full access since November. Seven months inside the infrastructure of a country’s largest carrier. Nobody noticed.

This wasn’t an isolated incident. This is the first full-scale cyber war in history.

And the lessons apply to every power grid, railway system, and telecom provider worldwide.

The Scale Nobody Talks About

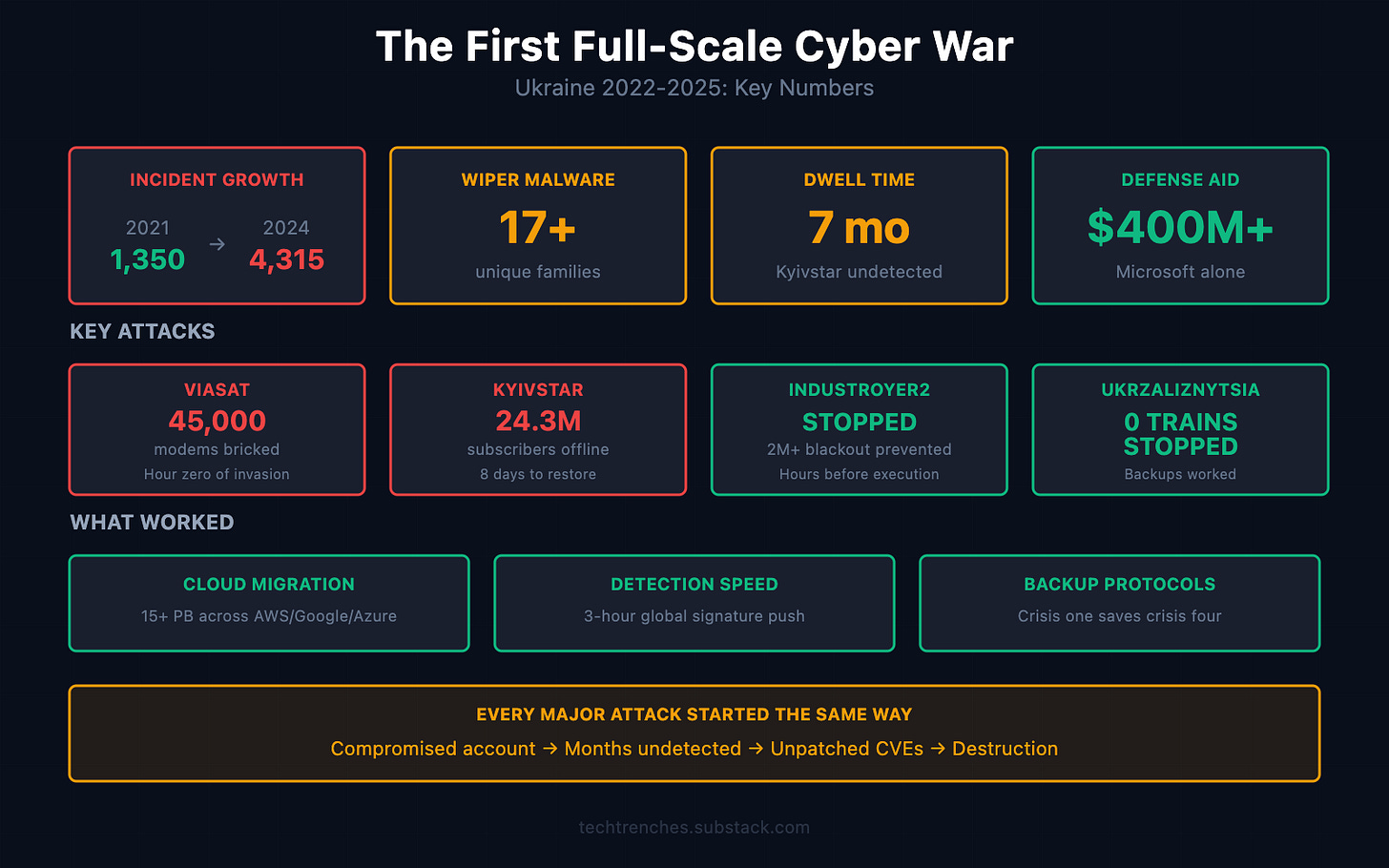

Between 2022 and 2024, Ukraine recorded over 9,000 cyber incidents. The trajectory, according to SSSCIP data reported by Infosecurity Magazine:

2021: 1,350 incidents

2024: 4,315 incidents

Growth: 220% in three years

Russia deployed 17+ unique wiper malware families: programs designed solely to destroy data beyond recovery. WhisperGate, HermeticWiper, CaddyWiper, Industroyer2, AcidRain. Each built for specific targets.

But here’s what Western coverage often misses: this isn’t one-sided aggression.

Ukraine hit back. Hard.

In July 2024, Ukraine’s military intelligence (GUR) claimed responsibility for a week-long DDoS attack on Russia’s banking system. Sberbank, Alfa-Bank, VTB, Gazprombank, the Central Bank. Users reportedly couldn’t withdraw cash from ATMs. In December 2025, anonymous hackers breached Mikord, a developer of Russia’s unified military draft registry. 30 million records. Source code, documentation, backups destroyed, according to investigative outlet iStories, which verified the breach. Mikord’s director confirmed the attack. Russia’s Defense Ministry denied any impact on the registry.

This is symmetric warfare. Both sides are hitting critical infrastructure. Both sides claim real damage.

The Attacks That Changed Everything

Viasat: The Hour-Zero Strike

February 24, 2022. 03:02 UTC. Exactly one hour before Russian ground forces crossed the border.

Attackers exploited a VPN misconfiguration at Viasat’s management center in Turin, Italy. They pushed AcidRain wiper malware to 40,000-45,000 satellite modems via legitimate software update mechanisms.

The result: Ukrainian military command and control went dark at the moment of invasion. Spillover disabled 5,800 German wind turbines and affected 9,000 French subscribers.

One misconfigured VPN. 45,000 modems bricked. Military communications disrupted during the most critical hour of the war.

SentinelOne researchers called it “the biggest known hack of the war.”

Industroyer2: The Blackout That Almost Was

April 8, 2022. ESET researchers discovered Industroyer2 scheduled to execute at 16:10 UTC against Ukrainian electrical substations. CaddyWiper was programmed to run 10 minutes later to destroy forensic evidence.

The malware implemented IEC 60870-5-104, the protocol used by electrical substation protection relays. It contained hardcoded IP addresses for eight target ICS devices.

If successful: a blackout affecting over 2 million people. The largest cyber-induced power outage in history.

It failed. CERT-UA, ESET, and Microsoft coordinated a defense based on lessons from the 2016 grid attack. The attack was stopped hours before execution.

The pattern: preparation from crisis one saved crisis two.

Kyivstar: When Security Investment Isn’t Enough

Kyivstar wasn’t some underfunded government agency. It was Ukraine’s largest private telecom, a subsidiary of Amsterdam-based VEON, with serious security investment.

Didn’t matter.

Sandworm penetrated the network in March 2023. By November, they had full access. On December 12, they executed, destroying the core infrastructure, wiping “almost everything.”

Vitiuk’s assessment: “This attack is a big message, a big warning, not only to Ukraine but for the whole Western world to understand that no one is actually untouchable.”

40% of Kyivstar’s infrastructure disabled. Services restored in phases over eight days. Losses estimated in the billions of hryvnia.

Ukrzaliznytsia: March 2025

With Ukrainian airspace closed since 2022, railways became the country’s lifeline. 20 million passengers and 148 million tonnes of freight in 2024.

On March 23, 2025, a “large-scale, systematic, non-trivial and multi-level” cyberattack hit Ukrzaliznytsia’s online systems. CERT-UA investigation found TTPs “characteristic of Russian intelligence services.”

Website and mobile app: offline. Long queues at physical ticket offices.

But trains never stopped running.

The difference from Kyivstar: backup protocols implemented after previous attacks. Systems built during crisis one carried through crisis two.

CEO Oleksandr Pertsovskyi: “The cyber-attack on the company was targeted and meticulously planned. However, not a single Ukrzaliznytsia train was halted for even a moment.”

Ukraine’s Counter-Offensive

Western media focuses on Russian attacks. The Ukrainian response gets less attention. The following operations were claimed by GUR or pro-Ukrainian hackers. Independent verification varies, and Russian authorities have denied most claims.

Tax Service, December 2023. GUR claimed it destroyed databases across 2,300+ regional servers. Configuration files “which for years ensured the functioning of Russia’s tax system” allegedly wiped. Russia’s Federal Tax Service denied any operational impact, though users reported access problems.

Planeta, January 2024. GUR claimed an attack on a state satellite data center. 280 servers allegedly destroyed. 2 petabytes of military-relevant weather and satellite data reportedly wiped. Supercomputers “not fully restorable due to sanctions.” Claimed damage: $10+ million.

Banking System, July 2024. GUR claimed a week-long DDoS campaign targeting Sberbank, Alfa-Bank, VTB, Gazprombank, Central Bank, plus VK, Discord, and the national payment system. Reports indicated ATM disruptions across Russia.

Russian Railways, March 2024 & June 2025. Multiple attacks reportedly taking down RZD’s website and app. Moscow Metro hit days after Ukrzaliznytsia attack in apparent retaliation.

Mikord Draft Registry, December 2025. Anonymous hackers (not attributed to GUR) breached Mikord, a key developer of Russia’s unified military registration system. The Moscow Times and iStories verified the breach. Mikord’s director confirmed the hack. The registry contains 30 million conscription records. Source code, documentation, and backups reportedly destroyed. Russia’s Defense Ministry called the reports “fake news.”

Grigory Sverdlin, anti-conscription organization Idite Lesom: “For several more months, this behemoth won’t be able to send people off to kill and die.”

The Vulnerability Patterns

Four years of cyber warfare exposed consistent vulnerability classes. These aren’t Ukraine-specific. They exist in Western infrastructure.

VPN and Remote Access

The Viasat attack exploited a VPN misconfiguration. Kyivstar’s breach likely started with a compromised employee account. CISA documented GRU exploitation of CVE-2018-13379 (FortiGate), CVE-2019-11510 (Pulse Secure), CVE-2019-19781 (Citrix). Vulnerabilities with patches available for 5+ years.

Dwell Time

Kyivstar: attackers inside for 7 months before execution. October 2022 power grid attack: Mandiant found attackers with SCADA access for up to three months.

Sophisticated adversaries don’t rush. Detection capabilities that can’t identify months-long intrusions are detection capabilities that don’t work.

Supply Chain

The Viasat attack weaponized legitimate software update mechanisms. CERT-UA documented at least three supply chain breaches in March 2024 energy sector attacks.

IT/OT Convergence

The October 2022 grid attack gained OT access through a hypervisor hosting a SCADA management instance. Attackers used native MicroSCADA binaries, living-off-the-land techniques. Mandiant: “a growing maturity of Russia’s offensive OT arsenal.”

Victor Zhora, SSSCIP Deputy Chairman, emphasized air-gapping between IT and OT as fundamental. Most Western utilities have moved in the opposite direction.

Centralization

The Mikord hack illustrates the pattern: centralization creates single points of failure.

Ukraine’s cloud migration (15+ petabytes distributed across AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure) proved more resilient than hardened on-premises facilities.

Deputy Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov: “Russian missiles can’t destroy the cloud.”

What Actually Worked

Cloud Migration. One week before the invasion, Ukraine’s parliament enabled government data migration to cloud. PrivatBank (20 million customers) migrated 270 applications and 4 petabytes in 45 days. Financial services continued throughout the war.

Detection Speed. Microsoft detected HermeticWiper hours before the invasion. Within 3 hours, signatures pushed globally. The Industroyer2 defense succeeded because CERT-UA, ESET, and Microsoft coordinated based on 2016 lessons.

Backup Protocols. Ukrzaliznytsia’s trains ran during attack because they’d been attacked before. Kyivstar took eight days to restore. The difference: systems built during previous crises.

Public-Private Partnership. Microsoft: $400+ million in aid. Google: Project Shield on 150+ websites. Cloudflare: ~130 government domains. AWS: Snowball devices shipped to Poland within 48 hours.

Carnegie Endowment: “delivering cyber defense at scale could only be achieved by private sector entities that owned, operated, and understood the most widely-used digital services.”

The Human Layer

Every major attack in this analysis started the same way: a person.

Kyivstar: likely a compromised employee account. Viasat: a VPN misconfiguration someone didn’t catch. The GRU exploits from 2018 and 2019 still work because someone hasn’t patched systems that have had fixes for five years.

Nation-state attackers don’t need zero-days when humans provide the access.

I manage distributed engineering teams from a US-based company, with engineers in Ukraine. We’ve operated through four years of this war. Our security isn’t optional: mandatory quarterly security training, BYOD policy with device management, password policy with breach monitoring, 2FA on everything without exceptions, access reviews when roles change.

None of this is exotic. All of it is enforced. The same principle applies to AI safety. I wrote about why AI creators are losing their legal shield in The Grok Precedent. Different domain, same lesson: policies that aren’t enforced aren’t policies.

The difference between “we have a policy” and “the policy is mandatory” is the difference between Kyivstar and Ukrzaliznytsia.

The companies that survived had one thing in common: policies that were actually followed, not just documented.

What This Means for Everyone Else

CISA Director Jen Easterly: “This is a world where such a conflict, halfway across the planet, could well endanger the lives of Americans here at home through disruption of pipelines, pollution of our water systems, severing of our communications, and crippling of our transportation nodes.”

It’s already happening. May 2025: CISA and NSA published a joint advisory. GRU Unit 26165 has been targeting Western logistics and technology companies involved in Ukraine aid since 2022. Targets include air, sea, and rail entities in NATO member states.

Water systems are being hit. CISA documented pro-Russia groups exploiting unsecured VNC connections in water facilities. The attacks “have not yet caused injury.”

Not yet.

The Math of Preparation

Ukraine’s experience validates a principle that applies beyond war:

Systems built during crisis one determine whether you survive crisis four.

The second blackout campaign in 2023 hit less hard because teams had backup power. The third in 2024: less disruption. The fourth in October 2025: near-normal operations despite 12+ hour outages.

Ukrzaliznytsia’s trains ran because they’d been attacked before. Kyivstar, despite security investment, had no institutional memory of crisis response.

Preparation compounds. Vulnerability compounds.

Every organization running critical infrastructure faces a choice: build systems during peace for crises that will come, or scramble during attacks with tools that don’t exist.

The cyber war in Ukraine isn’t just a regional conflict. It’s a live demonstration of what works when nation-state attackers target infrastructure.

The lessons are available. The question is whether anyone is paying attention.

If this analysis was useful, forward it to someone responsible for infrastructure security.

For engineering leaders: the systems that survive crises aren’t built during crises. They’re built before.